Lymphoma is a type of cancer that affects the lymphatic system, and it can occur in either humans or animals. The most common type of canine lymphoma is B-cell lymphoma, which is the most common type of canine cancer. Unfortunately, lymphoma is a serious diagnosis, and it often results in a short life expectancy. Therefore, many dog owners understandably want to know if their pet will suffer from this type of cancer.

It’s important to note that lymphoma affects all dogs differently, and some dogs may experience a wide range of symptoms, while others may show very few symptoms. In addition, some treatments may have severe side effects, while others may have little impact on the animal’s quality of life. Therefore, it’s important to understand the specifics of your pet’s condition before making decisions regarding their care. In this blog post, we will explore the question of whether or not dogs with lymphoma suffer, and what owners can do to ensure their

What Causes Lymphoma in Dogs?

Sadly, researchers are still unsure of what triggers or origins of canine lymphoma. According to some studies, lymphoma can develop as a result of exposure to harmful substances like magnetic fields or herbicides containing phenoxyacetic acid.

As a result of additional cancer-causing environmental factors, dogs can also develop lymphoma. For now, no one knows the exact cause. We’ll monitor this and let you know if we discover any new information.

Although the exact cause of canine lymphoma is unknown, there are treatments available if your dog has the disease.

Treating Lymphoma in Dogs

To restore your dog’s health for a while with the fewest side effects, treatments or disease remission are essential. Although not entirely gone, lymphoma is not present in any detectable amounts.

According to the College of Veterinary Medicine Purdue University, the most effective treatment therapy for dogs with lymphoma is chemotherapy because it helps to stop or hinder cancer cells from growing or dividing.

Chemotherapy is more effective than surgery for treating lymphoma in dogs because it can spread to multiple body parts.

The type of chemotherapy varies depending on the type of cancer. Some cases may require radiation therapy or surgery. For instance, the chemotherapy regimen UW-25 will be administered to canines who have multicentric lymphoma and enlarged lymph nodes.

The non-Hodgkin lymphoma chemotherapy protocol UW-25 is based on the CHOP protocol used in people.

The most efficient chemotherapy regimen for canines with cutaneous lymphoma is lomustine or CCNU.

As you can see, since canine lymphoma is similar to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in humans, many veterinarians and human doctors employ nearly identical chemotherapy regimens to treat their lymphoma patients.

Thankfully, chemotherapy usually does not make dogs as ill as it does humans. Dogs rarely lose their hair during this treatment, in contrast to humans who do. There are a few exceptions. Some dog breeds, including the Poodle, Bichon Frise, and Old English Sheepdog, are prone to hair loss.

The most frequent side effects of chemotherapy in dogs are decreased energy levels, diarrhea, and mild vomiting.

The answer, unfortunately, is not that simple. The prognosis will also depend on the stage of your dog’s cancer at the time of treatment, the particular treatment chosen, and how aggressive the lymphomas are.

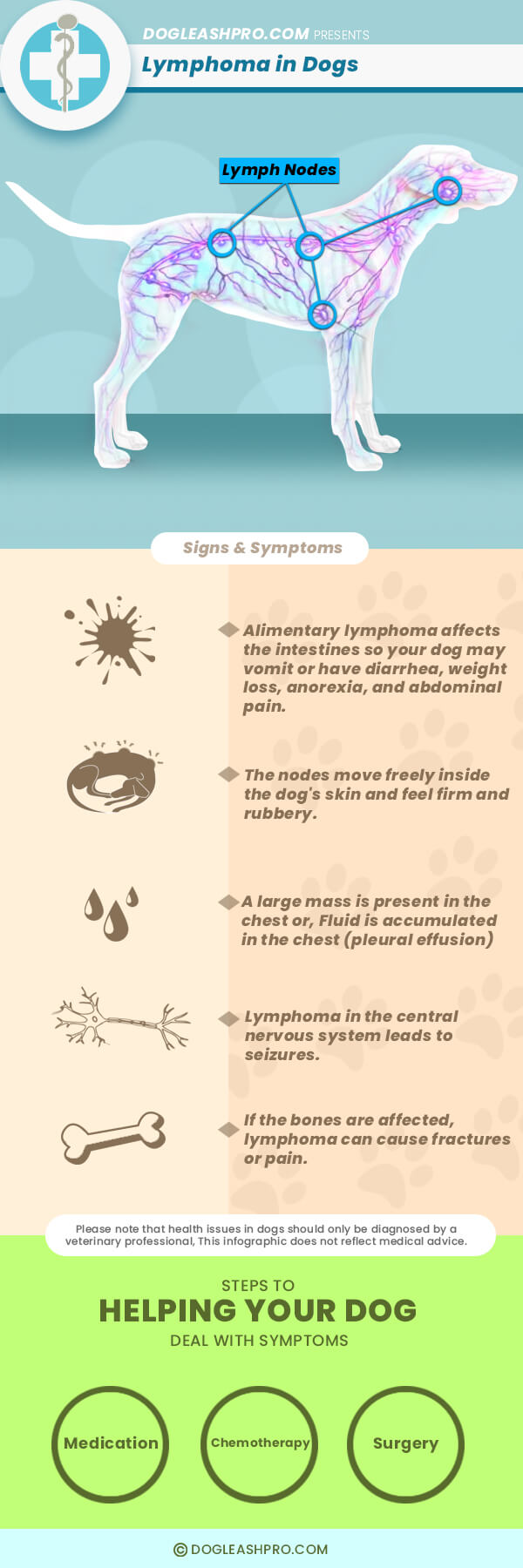

Respiratory distress symptoms are probably present if the extranodal lymphoma is in the lungs. In a similar manner, extranodal lymphoma in the kidneys may result in renal failure, lymphoma in the eyes may result in blindness, lymphoma in the brain may cause seizures, and lymphoma in the bones may result in pain or fractures.

Following a lymphoma diagnosis, some vets advise “staging tests” to determine how far the illness has spread throughout the dog’s body. These examinations, which also include bone marrow aspiration, blood tests, urinalysis, x-rays, and abdominal sonograms, aid veterinarians in understanding your dog’s overall health as well as the cancer.

Alimentary lymphoma, which makes up less than 10% of canine lymphomas, is the second most prevalent type of lymphoma. The majority of symptoms of gastrointestinal lymphoma are found in the intestines.

Here are the signs, tests, types of treatment, and prognosis data you need to know about canine lymphoma.

FAQ

What are the end stages of lymphoma in dogs?

Dogs with end-stage lymphoma may exhibit extremely lethargic behavior, vomit, have diarrhea, eat less or not at all, and lose weight. Because they are obstructing the throat, large lymph nodes can impair breathing. Your dog may exhibit noisy stertor breathing or difficulty breathing.

How do dogs feel with lymphoma?

Dogs with lymphoma frequently have lymph nodes that are three to ten times larger than normal. These swellings feel like a firm, rubbery lump that moves freely beneath the skin, but they are not painful. As multicentric lymphoma progresses, dogs may also experience lethargy, fever, anorexia, weakness, and dehydration.

How long does a dog have to live after being diagnosed with lymphoma?

Most canine lymphoma types have a life expectancy of just a few months. Depending on the treatment strategy, this is increased to an average of 612 to 12 months with chemotherapy protocols.

Do dogs act normal with lymphoma?

When a dog first develops lymphoma, they frequently appear healthy, so you might not observe any additional symptoms. One exception is that if your dog’s blood calcium levels increase, he might become lethargic, lose his appetite, and drink more water as a precaution against kidney damage.